“Why must this revolution happen in winter?” Raphaël quipped, raising his twinkling eyes from his hands, hovering over the trashcan bonfire. I chuckled and asked whether he had been coming to many of the weekend protests against France’s carbon tax. “Not all of them, because I often work on Saturdays. I’m a bus driver.”

Raphaël explained that he lived outside of Paris, and the spike in gas prices was too much for his family to bear. “The tax is nothing for people living in Paris. They all have the metro. All my family in the countryside felt this immediately.”

“Yes, we care about the climate, but justice, too,” he explains. “It’s the same battle.”

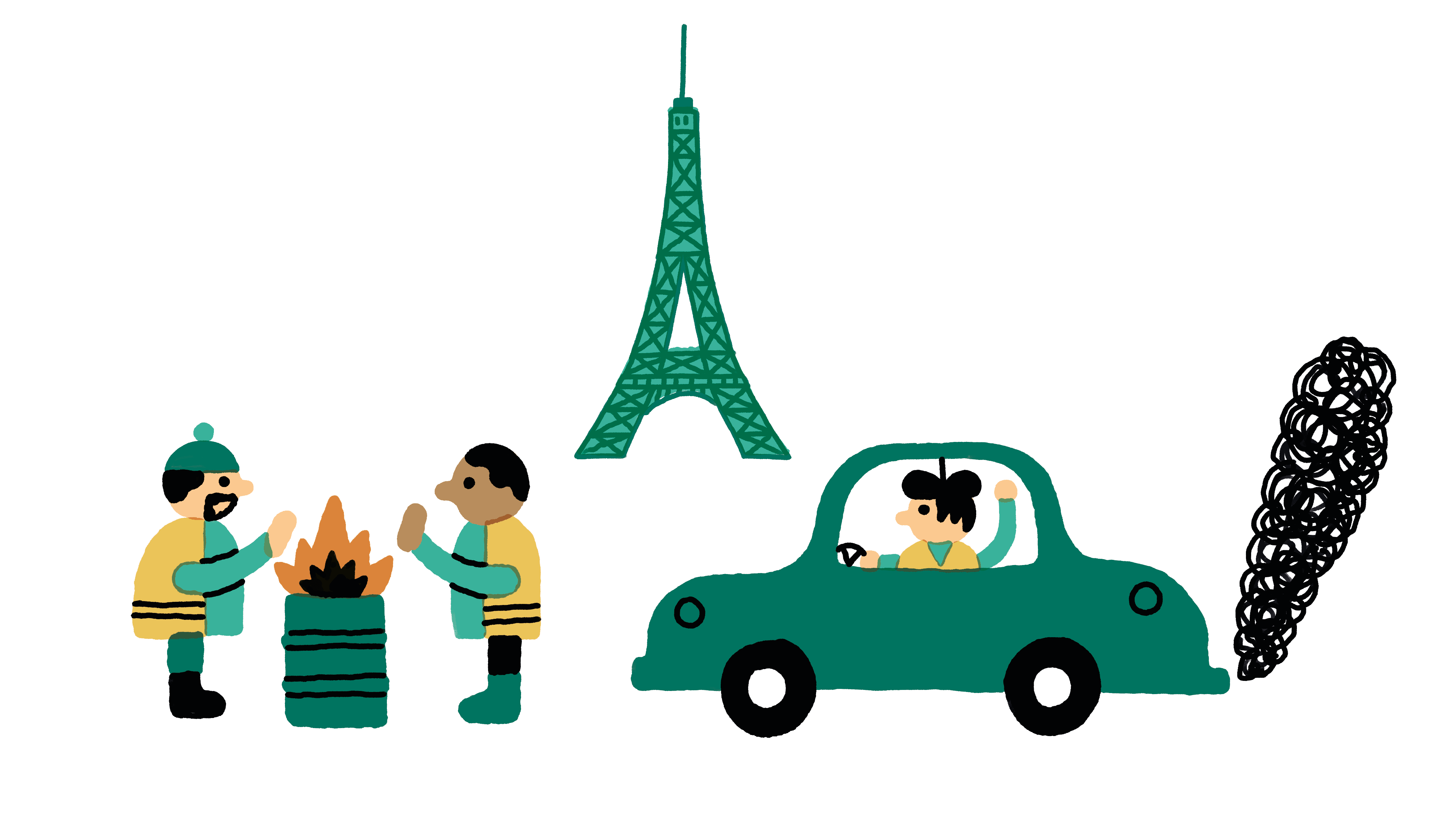

During the French protests that began in response to a rise in gas prices in 2018, I spoke with Raphaël and 30 other “yellow vest” activists over a few months at protests, meetings, homes and cafés. The activists were from all walks of life in France: I interviewed electricians, teachers, artisans, students, factory workers, janitors, nurses, retirees, veterans and more. Why are they called the “yellow vests”? All motorists in France are required to keep a yellow vest in their car to wear for emergencies. For Raphaël and millions of others, wearing the yellow vest became a symbol of protest. In interviews, I was interested in what drove them to mobilize and their views on climate change. Coming from the United States, a country that’s politically polarized over the topic of climate change, I expected the yellow vest activists to be right-wing opponents to climate policy. Yet I found something entirely different.

Like Raphaël, everyone uniformly supported climate action and was truly concerned about rising greenhouse gas emissions; however, they disagreed with the French government’s carbon tax approach, which they felt was unjust. In other words, they agreed on the “why” of climate action but disagreed on the “how” of chosen solutions – the very crux of decarbonization for the world at large.

Yes, we care about the climate, but justice, too. It’s the same battle.

More than 80% of global energy is sourced from fossil fuels. With increasing pressures to decarbonize and incentivize a “green transition,” some governments are raising taxes on fossil fuel energy. The crux of this solution is that energy costs (electricity, heating, cooling and gasoline) compose a significantly larger portion of lower-income household budgets. Increasing energy prices disproportionately burdens lower-income groups. France, a country that collects more carbon tax revenue than any other in the world, experienced this the hard way. In the fall of 2018, the French carbon tax rate took a scheduled increase, and, by proxy, national fuel costs rose as much as 23%. In response, millions took to the streets all over the country, blocking roads, roundabouts and gas stations. At their most contentious, certain groups vandalized national monuments, tore up streets and clashed with the police. The world watched, shocked, as the country faced its most hostile protests in decades.

Today, global energy prices are rising for a number of reasons, including a rebound in demand since the beginning of the pandemic, when fuel use plummeted. This increase in energy prices has governments around the world contending with backlash. A dwindling supply of coal in India is causing power cuts, sparking protests. Energy price protests and truck driver strikes in Spain have caused the Spanish government to secure emergency support funds. Many other governments across Europe, such as Greece, are subsidizing energy prices to support struggling households. In France, smaller yellow vest protests started breaking out over fuel-price spikes this fall.

This time, the French government responded quickly by capping gas prices and promising to send €100 “energy cheques” to roughly six million lower-income households. Since the original yellow vest protests, the French government has altered its decarbonization strategy. After President Emmanuel Macron froze the contentious fuel tax in late 2018, he announced the government would spend more than €5 million to create a citizens’ assembly on climate change that would advise the president on climate policy. Ten of the assembly’s proposals were adopted into law; another 36 were included, but in watered-down form.

France’s housing minister has since said the country is going to greater lengths to consider the social consequences of climate policies and to include workers who might lose their jobs in the energy transition.

Can climate policy be implemented with less conflict? In a world where fossil fuels have been pivotal in driving development, prosperity and, indirectly, progressive reforms, it is difficult to answer this question. When it comes to carbon taxes, the increasingly favoured design is the “tax-and-dividend” approach. In this model, rather than raising general government revenue or financing environmental programs, carbon tax revenues are redistributed to households in routine payments. Cheques can be graduated so that lower-income groups receive more money, making the system more socially just. Canada is already using a tax-and-dividend approach, and while opposition to the national carbon tax still percolates, it’s generally dwindling. Like Canada, France’s carbon tax had abundant exemptions for carbon-intensive sectors, but it saw much of the revenue going to corporations as a tax credit rather than back to the people, which further fuelled discontent among average consumers.

Carbon taxes will not solve climate change, however, as they are “market-fixing,” not “market-shaping.” They attempt to fix a market failure (by putting a price on emissions), rather than reshape the market to be inherently carbon-free. There is nothing wrong with market-fixing; it’s simply that market-shaping is more effective at transforming economies.

Fossil fuels were historic forces. Tapping them powered the industrial revolution and delivered many years of economic growth and prosperity. Fossil fuels shaped the very fabric and design of our modern world. As a fundamentally transformative force, their elimination will require fundamentally transformative market-shaping solutions, public investment that’s coordinated between multiple governments and the private sector, with the ultimate goal of shifting paradigms. Crucially, these policies must place the well-being of everyday people and workers whose livelihoods would disappear with decarbonization at the centre of these transitions or decarbonization may never happen. What might this look like in practice?

The French government recently bailed out a struggling French car company, Renault. Contingent upon receiving the funds, however, Renault is required to move toward EV battery production and keep certain factories in France open to support key jobs. Though small-scale, this kind of public–private sector coordination is necessary; the private sector receives capital to innovate, but it is conditional upon their moving toward carbon-free technologies and including workers in the process.

An economics of decarbonization must include an economics of inclusion to be successful. The good news is that many aspects of the transition (such as retrofitting buildings and constructing public transport) are labour intensive and will require abundant skilled workers. Small steps that support households struggling with increased energy costs and guarantee greener jobs for those in carbon-intensive sectors offer some hope.

With reports of energy price protests flaring up around the world and challenges with global economic recovery, I think back to the activists I met in Paris in 2019. For decarbonization to succeed, it must support average citizens like Raphaël. If not, they will continue to take to the streets. As Raphaël noted, “They cannot tax our walking.”

Daniel Driscoll is a political economist and PhD candidate at the University of California San Diego.