Two years ago, on a Monday morning in April, my phone rang. It was the teenaged daughter of a neighbourhood friend, asking if I could come to their house. Now.

Noting the police cars parked in front, I found my friend Leslie standing, in her sweats and slippers, on the high fence of her backyard, embracing the trunk of the magnificent balsam fir tree that towered over her property. Above her, harnessed to the tree, was a helmeted young man with a chainsaw dangling from his tool belt. Below her, on the ground, were two cops.

“I don’t understand why we’re cutting down trees like this when the city has declared a climate emergency,” Leslie said. The cop suggested she come down off the fence. She wasn’t budging. Stalemate hung in the air.

As she explained from her perch, Leslie had tried every legal avenue – writing to all the relevant offices at the city – to defend that tree, which her new neighbour had applied to remove to make way for a bigger and better house. This was her last resort: clinging to it for dear life. Its dear life.

That battle was lost; by the end of the day, that fir tree was firewood. And now a three-storey house with a footprint in excess of Toronto’s zoning bylaws stands where it once did. But the war is far from over. Now, more than ever, cities are recognizing the critical importance of the urban forest to their livability, and they’re working hard to translate that recognition into action.

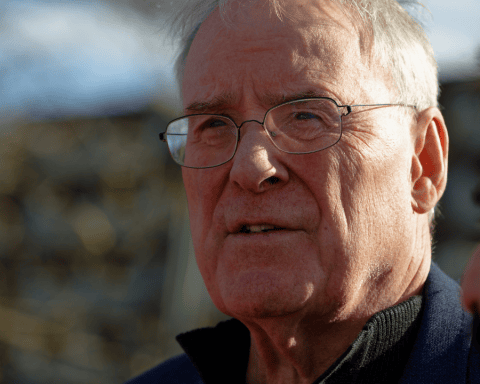

“Nobody disputes that trees are good,” says Marc Berman, a psychologist at the University of Chicago who researches the impact of urban vegetation on human cognition and emotion. “But the question – especially when budgets are tight – is how good? Why good? And are they worth it?”

City dwellers have always appreciated trees for the beauty they offer, the birdlife they harbour and the shade they cast over sidewalks in the dog days of summer. But in the context of the climate crisis, it’s their less visible benefits that are coming to the fore: their ability to sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, to reduce erosion and flooding, to absorb runoff and to mitigate the “heat island” effect that takes hold in a built environment of concrete and asphalt, air conditioners and cars.

Furthermore, as urbanization proceeds apace – the United Nations predicts that more than two-thirds of the global population will live in cities by 2050 – trees are proving essential to human health, filtering particulate matter out of polluted air and boosting mental health and overall well-being.

As the true value of the urban forest becomes more evident, most cities in North America have set expansion goals. But growing the canopy is not just a matter of planting more trees. It’s also about redressing inequities in the distribution of green space, challenging long-held assumptions about urban design and budgeting, long-term, for trees’ well-being.

![]()

As part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, U.S. President Joe Biden allocated US$1.5 billion to urban tree-planting projects, specifically targeting poorer, racialized neighbourhoods. The issue of “tree equity” is gaining currency, particularly in the U.S., where the disparities are most glaring. In 2021, American Forests, a national conservation non-profit based in Washington, D.C., launched a Tree Equity Score that correlates the physical characteristics of a given area – the canopy, surface temperature and building density – with socio-economic metrics like the income, employment level, age and race of its residents. The score, between zero and 100, reflects the equity of tree distribution.

According to American Forests’ data, white-majority neighbourhoods in the U.S. enjoy 33% more tree canopy than communities of colour. As the climate warms and extreme heat events hit cities, this divide becomes less a matter of fairness than of survival. Between 2011 and 2020, the heat-related death rate among Black New Yorkers was twice as high as that of their white counterparts. In the summer of 2022, Phoenix, Arizona, the hottest large city in the U.S., saw a record 359 heat-related deaths, with the highest rates among Black and Indigenous men. Phoenix has become the first city in the U.S. to publicly aspire to “tree equity” by 2030, meaning a city-wide score of 100.

“We’re trying hard to drive resources to the communities that need it most,” says Maisie Hughes, vice-president of urban forestry at American Forests. The colour-coded map of tree equity scores across the U.S. makes this possible. For Hughes, a landscape architect and a woman of colour, the project is as much about trees as it is about overturning the deeply racist “social construct of America.”

In recent decades, rising urbanization and climate disruptions have led to declining urban tree cover on all continents except Europe. Cities in North America are working to counter that trend.

Last November, New York City Council announced that it would be increasing the city’s canopy from the current cover of 22% to 30% by 2035. Phoenix, located on the arid Sonoran Desert, is aiming to boost its coverage from 10% today to 25% by 2030. On average, Canadian cities have more canopy coverage, with the National Capital Region (which includes Gatineau Park) leading the pack at 46%, followed by Halifax at 43%. Toronto is aiming for 40% tree canopy by 2050, up from the roughly 28% it’s at today. But there are countervailing forces. A single ice storm took out 900 trees in Montreal last April, and the city – which announced the planting of 500,000 new trees in its 2020–2030 Climate Plan – has had to fell thousands of trees blighted by the emerald ash borer, an invasive species that has decimated the ash population across North America over the last two decades.

But the successful urban forest is not just a matter of numbers. In 2005, Los Angeles mayor Antonio Villaraigosa announced with great fanfare that his city would be receiving a million new trees. The plan didn’t account for the cost of water, or the fact that most trees would have to be planted on private land and require the cooperation of citizens. When Villaraigosa left the mayor’s office eight years later, L.A. was only some 400,000 trees richer.

Roughly half of the urban land available for trees in North American cities is privately owned. Conserving and expanding the canopy requires a public that is educated about the importance of trees and willing to help maintain them. Grassroots greening initiatives abound, says Danijela Puric-Mladenovic, a professor of urban forestry at the University of Toronto and co-founder of Neighbourwoods, a project that helps neighbourhoods, school boards and churches create inventories of the trees on their properties and monitor their health and growth.

But while public support of the urban canopy grows, cities continue to cave to the powerful forces of development. Despite its lofty forest-expansion ambitions, Toronto has seen its portion of plantable space decrease in the last decade and impervious land cover increase.

We’re trying hard to drive resources to the communities that need it most.

—Maisie Hughes, vice-president of urban forestry, American Forests

“Planning topples everything,” says Puric-Mladenovic. She says that many North American cities, stuck in a 1950s mentality of “develop first and plant second,” are still building concrete jungles, like the condominium forest of CityPlace in downtown Toronto, that offer nowhere near enough green space and suburban subdivisions that amount to a mass of housing wrapped around one woodlot or baseball diamond. Puric-Mladenovic calls the practice of planting tall trees in the same path as hydro poles – necessitating the regular butchery of their limbs – emblematic.

Given the huge pressure on urban land, cities have to fully integrate, even prioritize, trees in their planning blueprints. Lots of little parks don’t cut it; Puric-Mladenovic says the best way to ensure tree health is to create green swaths, like Toronto’s ravine system, in which species and water systems connect and biodiversity flourishes. Thanks largely to their less car-centric design, European cities offer a model that combines density with impressive amounts of green space.

Help them grow

Cities also need to take maintenance seriously. Trees cause serious damage when they fall or when their roots compromise building foundations, underground waterpipes or pavement. A growing number of cities are using Lidar (light detection and ranging) data, a three-dimensional system that models individual trees rather than the canopy as a whole, to ensure that trees reach maturity, which is when they perform best: throwing the most shade and trapping exponentially more pollutants than young ones.

In defence of trees, some cities are now assigning a dollar value to their contributions. In its most recent strategic forestry plan, for instance, the City of Toronto assesses the “structural value” of its forest – defined as what it would cost to replace it – at $7 billion and estimates that it provides $28.2 million annually in ecological services (pollution removal and energy savings) while representing a carbon storage benefit of $25 million. But cost-benefit assessments don’t capture the full picture.

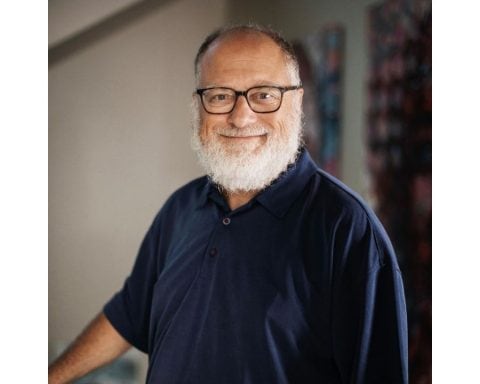

“You can’t just take the bean-counter view,” says Hashem Akbari, an environmental engineer at Concordia University. It’s an interesting perspective, coming from someone who deals largely in numbers and efficiencies. As co-founder of the Heat Island Group, a research lab at the University of California, Akbari has spent much of his career considering which measures – from building materials to roof construction to city planning – are most effective in reducing urban heat.

He says that trees in Canadian cities may provide energy savings of around 20% through the shade they create in summer (reducing the need for air conditioning) and the windbreak they offer in winter (insulating buildings from the cold). This benefit, he says, is more significant than their carbon performance, given that urban trees in Canada – battered by road salt and dog pee – live considerably shorter than their cousins in the wild; when they die and decompose, the carbon they sequestered is released back into the atmosphere.

Nonetheless, Akbari is unequivocally pro-tree. “There are so many aspects of the tree you can’t quantify,” he says.

Psychologist Marc Berman studies some of those unquantifiable aspects in the Environmental Neuroscience Lab he runs at the University of Chicago. His research suggests that trees go a long way toward restoring a kind of neurological balance in people living in the “arbitrary” environment of the city. Experiments conducted in his lab have shown that even brief engagements with nature – like a walk in a park – boost the brain’s capacity to focus and to remember.

The findings have profound implications for city planners and leaders. In addition to carbon, energy and pollution services, the canopy’s more subtle benefits translate directly into economic ones: improved human productivity, higher property values, reductions in healthcare costs and crime rates.

“Green space must be treated as a necessity, not an amenity,” Berman says. “There has to be a revolution in how we think about these things.”

This story is part of the Sustainable Cities section in our Spring 2024 issue.