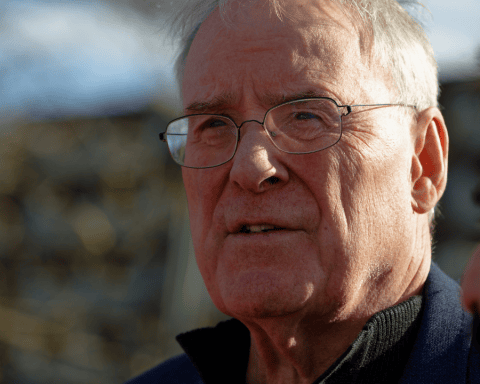

Wei Jiang is the Arthur F. Burns Professor of Free and Competitive Enterprise at Columbia Business School and a faculty leader at The Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. Center for Leadership and Ethics.

The official theme of this year’s International Women’s Day is Women in Leadership: Achieving an Equal Future in a COVID-19 World. In announcing the 2021 focus, UN Women pointed out that the countries that were most effective in curbing the health and socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 are led by women. Yet women are heads of state and government in only 20 countries worldwide.

The lack of women in leadership is mirrored in the corporate sphere, where long tenures are slowing the influx of varied perspectives and skill sets among board directors. But a simple solution to the problem exists.

I recently completed an analysis of the boards of all public firms and the largest private firms in the U.S., dating back to 2000 and covering 4,000 to 5,000 firms each year. Prior to the financial crisis, women held only about 8% of director seats. Since then, the figure has increased to 19% on public boards in 2019, while little changed for private firms. Among public corporations, women constituted about 30% of new board members over the three most-recent years, but total gender diversification was slowed by two factors: first, some women left board positions as others joined, providing only a small gain; second, a significant number of corporate boards enacted a one-time expansion to make room for extra women directors. However, expansion isn’t a sustainable strategy for deeper diversification. Turnover is necessary to make way for more women and other diverse candidates.

While the study was limited to U.S. corporations, the principle holds true for established boards in any location: long board tenures slow the rate of diversification from contemporary candidate pools. In the U.S., the annual turnover rate for board directors between 2008 and 2019 was 8.9%. By comparison, the turnover rate for CEOs was 12.5%. More importantly, a significant proportion of the board directors have enjoyed extraordinarily long tenure. For example, nearly a quarter of directors held their seats for 10 years or more, and 8.5% held their seats for at least 20 years. Percentages of CEOs holding their positions after 10 and 20 years were 3% and 1%, respectively.

Even a board that does a terrific job diversifying new recruits can’t rely on natural turnover. If it does, rotation – and thus diversification – will happen at a glacial pace, causing numerous problems. As with government leadership related to COVID-19, corporations need diverse management perspectives on both crisis and non-crisis situations. In fact, previous research shows women directors contribute specific functional expertise that was previously missing from corporate boards.

Several European countries and California have legal mandates for increasing board diversity, and numerous public companies have board diversity goals as part of their corporate social responsibility (CSR) commitments. But simply nominating women to fill the few available seats does little to diversify the full board and may restrict a firm’s ability to represent other strategic needs on the board. A better solution is to focus on increasing director turnover, ensuring a consistent flow of available seats for diverse candidates with a range of contemporary skills and the knowledge necessary to innovate the business. Numerous studies have found that companies with greater diversity also demonstrate more innovation. If you want to understand the risk of not refreshing a board’s perspective, consider Blockbuster’s decision not to purchase Netflix, Kodak’s failure to embrace digital photography, and McGraw Hill’s foot-dragging on S&P Global before the spin-off. In all these cases, the board members were from an era when the “old” business model was successful, and they didn’t fully appreciate the disruptive forces of new technology.

Corporations can shift board culture away from long tenures by placing hard or soft caps on terms. This would neutralize any stigma that might currently be associated with directors who resign after just a few years. In France, independent directors lose their “independent” status after a set number of years, which is another way to encourage turnover via external pressure. Other rules could encourage turnover while leaving the door open to directors of particular, long-term value. For example, directors could be required to take a hiatus at the end of their terms but stand for re-election in future years. Or, they could stand for re-election at the end of their terms only if the board also nominates alternate candidates for the seat.

Regardless of the method, if we’re to release the bottleneck holding back women in leadership at the level of corporate boards, achieving regular turnover is the key.