The COVID-19 lockdown, while in many ways stultifying, stressful and depressing, also had some unexpected upsides. As human activity waned, nature came to the fore. City dwellers were suddenly aware of birdsong. On the epic dog walks that became the highlight of our days, random strangers would comment on how blue the sky was, how clear the air, how resplendent the ravine in spring.

Climate activists noted, with some combination of cynicism and optimism, how quickly the world managed to mobilize in the face of an immediate threat. And indeed, the radical change in human behaviour – the grounded planes, eliminated commutes, reduction in industrial production and power generation – had an impact. By early April, daily global CO2 emissions had dropped by 17% compared with mean levels in 2019.

But the gazillion-dollar question remains: Will the massive disruption of this pandemic serve to fuel our collective determination to combat climate change or undermine it? Will the political response to the crisis be conceived in terms of a planetary recovery or a short-term economic one? In the language of our leaders, will we decide to build back fast or will we build back better?

Europe, for one, seems to be opting for better. The EU’s recovery package, which has been built into its 2021 to 2027 budget, is unprecedented not only in its level of spending but also its commitment to climate and ecological goals. Vast in scope, it aims less to kickstart the economy than to fundamentally reshape it and place it on a greener, more sustainable footing.

It wasn’t clear that things would go this way – that the pandemic would supercharge Europe’s climate ambitions. Last December, as local health authorities were beginning to report cases of a mysterious pneumonia-like virus in Wuhan, China, the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, was presenting member states with the commission’s most ambitious climate policy package to date: the European Green Deal. With an overarching goal of climate neutrality (zero emissions) by 2050, the proposals left no sector of the European economy – transportation, manufacturing, energy, construction, agriculture, digital technology – unturned.

But as the virus spread across the globe, voices critical of the deal grew louder: surely now was not the time for massive climate investment, surely policy-makers needed to focus on the immediate health and economic crises. Not surprisingly, this position was articulated most forcefully by the member states that felt they had the least to gain from any green deal: coal-reliant Poland and Romania, the pro-nuclear Czech Republic. But by the end of April, environment ministers from 17 European states had signed an open letter urging the EU Commission to address Covid-19, biodiversity loss and climate change as one. They framed the Green Deal as a growth strategy, “able to deliver on the twin benefits of stimulating economies and creating jobs while accelerating the green transition in a cost- efficient way.”

The economic rationale is important, given the scale of the spending that was announced in May: a €750 billion recovery package on top of a €1.1 trillion budget, totalling €1.8 trillion, 30% of which must be spent on climate action: investing in renewable energy, retrofitting buildings and expanding biodiversity through protection and restoration programs.

That spending will have to pay off, as, unlike the budget itself, which is generated largely through member states’ contributions, the lion’s share of the recovery funding will be borrowed on capital markets and will have to be repaid. Backers of Europe’s green recovery budget – from German Chancellor Angela Merkel to IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva to former Bank of England governor Mark Carney – see this as a safe bet, not only because borrowing costs are low, but because investments in things like renewable energy and building efficiency are virtually fail-proof. They generate jobs, boost energy security (reducing dependency on Russia in the European context) and are not doomed to end as stranded assets of a carbon bubble.

The EU Commission is considering supplementary funding of its recovery package through a suite of measures that amount to 21st-century sin taxes – on non-recyclable plastics, carbon-heavy imports and digital behemoths like Apple and Facebook. These proposals are still under discussion but reflect an unassailable commitment to back the EU’s climate target with a level of investment that makes it realizable. It’s also determined to stay on track; last week the EU Commission raised its stepping-stone target for 2030 from a 40% to 55% reduction in greenhouse gases over 1990 levels, based on a cost-benefit analysis that deemed this more ambitious target “realistic and feasible.”

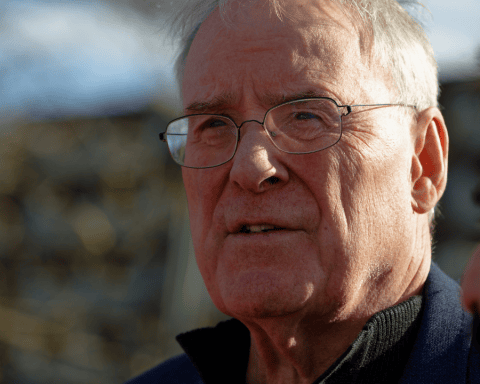

“It’s hard to overstate what a breakthrough this is,” says Brook Riley, a Brussels-based Scotsman who is head of EU affairs for Rockwool, a Danish manufacturer of stone wool insulation. The breakthrough Riley is referring to is the EU’s net-zero objective – which, unlike most major policy decisions at the EU, did not reflect a compromise position but rather a unanimous endorsement by all 27 states of the most ambitious goal on the table.

Rockwool’s insulation, derived from volcanic rock, is one of many low-carbon products destined to play a major role in the coming overhaul of Europe’s building stock, which currently accounts for one third of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions. Riley is seeing a frenzy of activity as states scramble to draft green recovery plans in a bid for their share of the €312 billion in grants to be disbursed in the coming months.

“It’s a race to figure out what are genuinely green investments, and that’s where we may see the cracks in the windscreen,” Riley says. “The administration of this will be very complex. There is no shortage of funding and no shortage of projects – it’s a matter of matching them.”

Critical to the success of this project is buy-in from the diverse states that make up Europe. The richer countries that traditionally support climate investment will receive a smaller portion of the green grants but can use political leverage – through the possibility of vetoes – to ensure that the poorer ones, which benefit more, actually use them wisely. There may be lessons in this kind of engineered solidarity for Canada.

“Poland has been wedded to coal much like Alberta is to the tar sands,” says Riley, “but Poland sees the writing on the wall.” By signing on to the net-zero goal, Poland entitles itself to a much higher level of financial support from the EU with which to finance the inevitable transition.

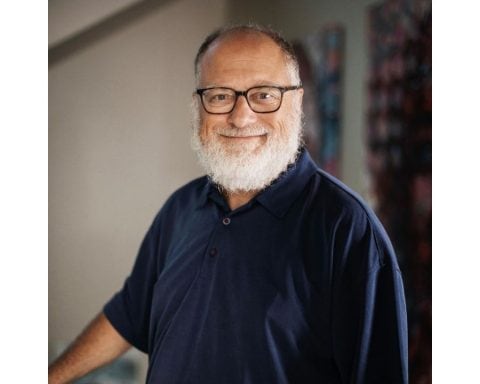

Isabelle Turcotte, director of federal policy at the Pembina Institute, the Ottawa-based clean-energy think tank, sees in the EU’s strategy a workable prototype for attaching green strings to recovery investment as well as a unity of purpose that Canada has yet to achieve.

“The disruption was already there,” says Turcotte, referring to the turbulence on the global oil and gas markets even prior to the pandemic. “Now we need to unite Canadians and support all workers in this transition.”

"We’re all in this together,” she says, echoing a trope that is suffering overuse in this pandemic. But the attitude will need to prevail if we, too, are to reach our own government’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2050. Europe may well show us the way.

Naomi Buck is a Toronto-based writer.

With the support of the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany in Canada.