Hero: Interface

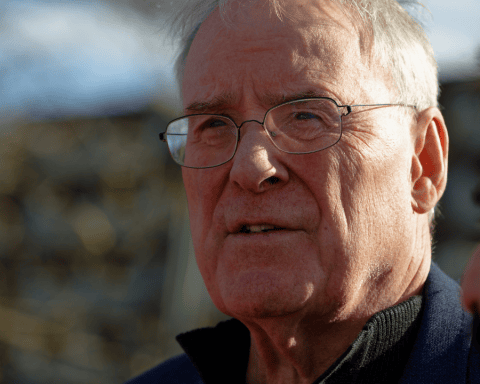

Ray Anderson set an ambitious target in 1994.

The founder and chief executive of Interface Inc. had just read Paul Hawken’s The Ecology of Commerce, which excoriates business for plundering the earth’s resources but also argues that corporations hold the keys to a more sustainable future.

Moved by Hawken’s indictment, Anderson vowed that Interface, one of the world’s largest makers of carpet tiles and thus a heavy petrochemicals consumer, would shrink its carbon footprint and other environmental costs to zero by 2020.

Anderson died in 2011, but his Mission Zero lived on. So much so that Interface was able to proclaim in November that it had met the target a year ahead of schedule.

Mission Zero began with a focus on reducing waste, from carpet scraps to industrial effluent. Interface has nudged a nylon supplier to produce a yarn with recycled content. It has worked on ways to stick carpet tiles to a floor without glue and replace natural gas with landfill gas.

The Atlanta-based company estimates that it has cut the carbon footprint of its carpet tiles by 69% over the past 25 years and virtually eliminated greenhouse gas emissions from its operations. Its factories in the U.S. and Europe are now almost entirely powered by renewable fuels.

“We’ve transformed our supply chain and our products, and we’ve implemented new business models,” the company said.

“Many others from our industry and beyond have followed us, creating a powerful ripple effect that exceeds our original ambitions.”

In 2017, Interface unveiled its Proof Positive carpet, which it claims is the world’s first carbon-negative carpet tile – in other words, it takes more carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere than it puts in. The raw material for the tiles stores carbon for at least a generation and can then be recycled to create new tiles.

“At Interface we can see a not-so-distant future in which architects, designers and businesses collaborate to create spaces with climate change in mind by choosing materials that will reverse global warming,” said Interface’s chief innovation officer, Chad Scales.

Interface is no bit player. It has 40 showrooms around the world and factories in Australia, China, Ireland, the Netherlands, Thailand, the U.S. and the U.K. Sales topped US$1 billion in the first nine months of 2019.

“What started out as the right thing to do quickly became the smart thing,” Anderson told a business conference in 2005. Which raises the question: if a company of Interface’s size can clean up its act, why aren’t many more following in its footsteps?

Zero: The Blackstone Group

With healthcare costs and income inequality among the top issues in this year’s U.S. election campaign, it’s hard to imagine a more tempting target than a Wall Street fund accused of ambushing working-class Americans with surprise medical bills.

That is precisely the allegation levelled by the House of Representatives’ energy and commerce committee against physician staffing and ambulance companies owned by The Blackstone Group and two other private-equity firms. Announcing an investigation into the three firms last fall, the committee asserted that “surprise billing has devastated the finances of households across America . . . Every day we hear stories about families who have endured financial and emotional devastation.” According to the committee, one in five emergency-department visits and 9% of elective inpatient care at in-network facilities end in a financial shock to the patient.

The extra costs typically arise when patients receive treatment at a hospital linked to their health insurer but are unaware that the hospital has contracted some services to out-of-network providers. In addition, doctors and hospitals sometimes refuse to accept the fees set by a patient’s health insurer. They then opt out of the insurance network and bill patients directly for the extra amount.

Blackstone and the other Wall Street funds have been called out because of their sizeable investments in medical-service contractors. Blackstone bought TeamHealth, America’s largest physician staffing company, in late 2016 for US$6.1 billion.

After the acquisition, “low-income patients faced far more aggressive debt collection lawsuits,” wrote non-profit newsroom ProPublica in late 2019, though TeamHealth denied a change in legal strategies.

Blackstone defends itself by noting that less than 0.16% of all TeamHealth claims result in surprise bills. According to a letter obtained by The Hill, Blackstone opposes any move to cap bills on the grounds that it would lead to damaging cuts in payments to doctors and hospitals. Instead, the private-equity firms have proposed independent arbitration.

After the ProPublica exposé, the company shifted tactics and issued a statement saying it would no longer sue patients and would drop any existing lawsuits.

Blackstone, led by hard-driving and flamboyant Stephen Schwarzman, manages more than half a trillion U.S. dollars. Its prime goal, obviously, is to produce the highest possible returns for its investors. But doing so on the backs of Americans’ medical bills tarnished its reputation at a time when pension funds and other institutional investors are under mounting pressure to demonstrate social responsibility. Other private-equity firms profiting off essential social services – and, for that matter, every other company – might wish to take note.