Of all Donald Trump’s misguided policies, few will cause more lasting damage than his drive to reverse the fight against climate change. Ditching the Paris Agreement, propping up domestic coal producers and easing pollution rules for cars and power plants are just some of the ways the former U.S. president has cossetted the fossil fuel industry.

Thankfully, others – including some in the business community – have been moving forcefully in the opposite direction. One notable example is Storebrand, Norway’s largest private fund manager, which last August became the first sizable investor to divest from businesses that continue to lobby against tougher environmental rules.

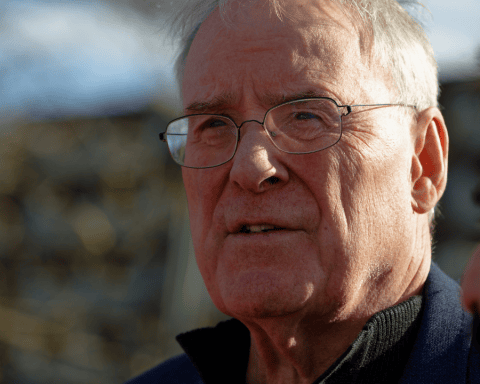

“Climate change is one of the greatest risks facing humanity, and lobbying activities which undermine action to solve this crisis are simply unacceptable,” said Jan Erik Saugestad, Storebrand’s CEO. InfluenceMap, a U.K.-based think tank, estimated in March 2019 that the world’s five largest oil and gas companies measured by market value – BP, Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron and Total – spend almost US$200 million a year on efforts to delay, control or block policies designed to tackle climate change.

“The Exxons and Chevrons of the world are holding us back,” Saugestad noted, referring to two of the five companies whose shares Storebrand has dumped. The other three are Anglo-Australian miner Rio Tinto, German chemicals manufacturer BASF and Southern Co., an Atlanta-based electric utility.

Storebrand, which manages more than US$90 billion in assets, has also sold its stakes in another 22 companies – mostly power utilities, chemical companies and oil producers – that fall short of a tougher slate of climate policies that it recently adopted. Among the new criteria is a commitment not to invest in companies that derive more than 5% of their revenues from coal or oil sands.

Storebrand’s moves reflect mounting pressure on institutional investors to take a stand on climate change. A majority of Chevron shareholders supported a resolution at the company’s 2020 annual meeting that sets tougher disclosure standards on climate-related lobbying activities. Proxy Insight, which tracks corporate governance issues, reports that shareholder support for climate-lobbying resolutions averaged 47.2% last year, more than double the 21.4% recorded in 2019.

Saugestad put it well: “Investors need to be responsible and proactive in accelerating the green transition. We are not passive actors awaiting the pending systemic harm that climate change will unleash.”

Zero:

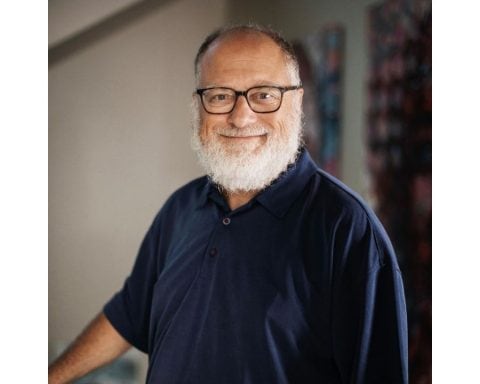

There is much to admire about the gig-economy companies that have woven themselves into our everyday lives over the past decade. Uber and Lyft have revolutionized urban transport. Instacart enables us to shop for groceries without ever leaving home, while DoorDash delivers tasty restaurant meals to our front doors, a special boon during the pandemic.

When it comes to labour practices however, these companies belong more in the 19th century than the 21st. Their drivers and personal shoppers work long hours for precious little reward. Because these workers are classified as independent contractors, they receive few if any of the normal workplace benefits, such as minimum wages, health or unemployment insurance, and parental leave.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, estimate that Uber and Lyft saved US$413 million in their state alone between 2014 and 2019 by not paying unemployment insurance premiums. More recently, the companies have been accused of violating a law passed by the state legislature last January that tightens the criteria for classifying workers as contractors.

None of that has stopped Uber and other app-based companies from fighting to preserve their workers-come-last business model. Indeed, they cranked up the pressure ahead of last November’s U.S. elections by pouring close to US$200 million into backing a California ballot initiative, known as Proposition 22, that would dilute the worker gains contained in last January’s law.

The companies contended that regulators should treat app-based businesses as technology platforms, not transport providers or food delivery services, because their workers have the flexibility to log into or out of the employer’s app at will. Uber warned that it would have little choice but to raise prices and limit services if Proposition 22 failed to pass.

Voters ended up approving the proposition by a 16-point margin. But that doesn’t make it fair on the workers.

Critics predict that Proposition 22 will reinforce the inequalities that have become a tinderbox of modern society, especially in the U.S. The UC Berkeley researchers concluded that, under the proposal, Uber and Lyft drivers would earn a mere US$5.64 an hour after factoring in down-time and expenses such as fuel and maintenance. Proposition 22 could also set a troubling precedent by encouraging deep-pocketed companies to take their cases directly to voters when they come up against laws they don’t like.