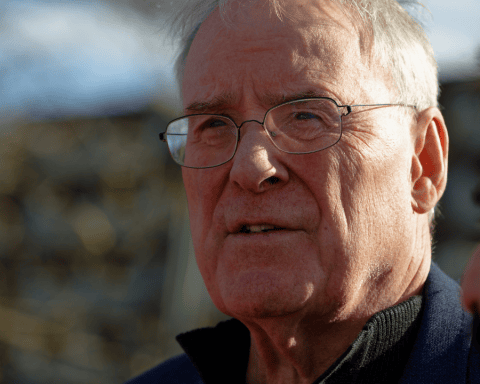

Beth Sanders, author of Nest City, works with citizens, government, business and community organizations looking for practical ways to navigate the complexity of city life.

Transition, by its very nature, is about feeling uncomfortable. If we’re comfortable, that likely means nothing is changing, because we’re enjoying the ease of the status quo.

Cities everywhere have to negotiate and navigate the complexity that comes with the different views and perspectives that make consensus on climate action a challenge. Is an energy transition needed? What actions are reasonable? Who should act, and when? Who should pay for it?

This is particularly difficult for cities at the epicentre of conventional energy-centred economies, such as Edmonton and Calgary. Local governments, business communities, community organizations and citizens give me a call when they are faced with this sort of challenge and realize they don’t know how to work together. I get invited into the heart of city conflict, over and over again, and I’ve found that bringing these historically divided groups together is a profound way for cities to make choices and act. Three principles guide my work at any scale, from small projects, such as supporting city hall and developers to create new infrastructure cost-sharing strategies to accommodate increased density, to the work of planning a whole city.

City work belongs to all

Cities are a messy web of relationships and interests, desires and priorities, where no single person – or sector – has control over the future. Government, business leaders, community organizations and citizens have unique and interconnected roles to play in legislating, innovating and making sure our cities serve their citizens well. Leadership comes from those who convene and connect these roles with each other.

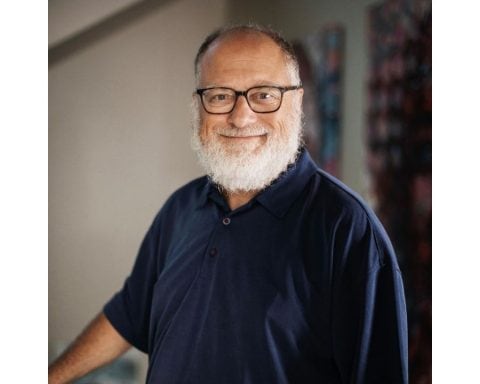

Jorge Garza works with the Community Climate Transitions team at Tamarack Institute, a 19-community climate transition network. Building on their track record of supporting a movement of 330 communities that have reduced poverty for more than one million Canadians, they are now focusing on a just and equitable energy transition. The climate network collaborates with communities to localize the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and build their capacity to host robust community engagement, develop a community-wide common agenda, and track and report on outcomes.

When it comes to integrating the perspectives of government, business leaders, community organizations and citizens, Garza observes that “systematically, we are not coordinated in our cities in ways that are inclusive and informative. Everyone needs to be involved in the process of changing. Government, business, everyone. We’re not there yet.”

Instead of thinking we each need our own plan, successful cities knit the various plans together.The learning edge for climate work is to bring community, government and business together in ways that allow us to hear each other and choose to act together. Town hall meetings are insufficient because we need to build our capacity to roll up our sleeves and get to work with people we don’t usually work with, not just talk at them. Tamarack’s work is vital to build our cities’ capacity to engage with each other and make a difference.

Practise thinking differently

Transition is a tricky business because it asks us to think differently not just about our energy use but about ourselves – and to be engaged in a process of changing.

As a director in what was then the City of Edmonton’s Urban Form and Corporate Strategic Development Department, Kalen Anderson led the development of Edmonton’s City Plan. She was equipped with a carbon budget to guide city government choices and accountability tools to connect the plan’s goals with budget decisions. Anderson invited her city to think outside the box as they created the plan for the capital of Canada’s oil and gas province, establishing policy direction for the entire municipal corporation, rather than only the city planners, with the expectation that everyone will work together to achieve climate goals.

Now, as executive director of the Urban Development Institute–Edmonton Metro, Anderson focuses on how to build the city the plan envisions. Net-zero construction, for example, increases the cost of buildings. According to Anderson, “We need to look at ways to reduce other costs, such as adjusting infrastructure standards. A series of thoughtful trade-offs are needed.” When it comes to housing, if those trade-offs aren’t made, we will have a city out of economic reach to its citizens. Will citizens tolerate paying more up front for net-zero homes or narrow streets with fewer parking spaces to avoid escalation in housing prices? Will policy-makers have the fortitude to work through potential resistance to new ideas and make the necessary changes?

While Edmonton thought differently about how to plan for a climate-resilient city, the work is just beginning. To implement its plan, it will need to step into polarizing conversations and make the choices that come with trade-offs.

The currency of city improvement is relationships

The cultivation of meaningful relationships is how we learn to work well with ideas and interests beyond the status quo.

Indigenous business leader Aaron Aubin is a Kwakwaka'wakw person living in the traditional territory of Treaty 7 First Nations and Métis Nation of Alberta Region 3. From Calgary, he operates a consultancy that supports Indigenous nations, governments and businesses throughout Canada. Aubin advises that cities and businesses benefit economically and culturally when they engage in conversations with Indigenous people: “Across Canada, Indigenous Peoples’ ways of knowing and doing are essential to the dialogues on how to build more sustainable and inclusive cities.”

The energy transition is an opportunity to incorporate Indigenous knowledge into our city-improvement work by crafting relationships of reciprocity with Indigenous Peoples, their governments and Indigenous-run businesses. When we reach out to create and sustain relationships with other interests, we strengthen our collective capacity – through our connections with each other – to take wise climate action.

Opportunity for economic and cultural transformation

Climate action can serve as an opportunity for economic and cultural transformation – if we are willing to work with others in ways that feel unfamiliar, awkward and even tense. Feeling comfortable may well mean we’re not doing anything new, and if we’re not doing anything new, then we’re not participating in our transition. The hard work ahead: learning how to work well together. Our survival depends upon it.