Businesses are suffering an unprecedented disruption. Every corporation is consumed with issues arising out of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has put their relationships with each of their stakeholders – employees, creditors, suppliers, regulators, shareholders – in stark relief.

During this period of turbulence, stakeholders are looking to boards of directors to address the impacts of the coronavirus. How boards balance and prioritize those stakeholders has to shift with shifting circumstances, just as boards are forced to think about the long-term sustainability of their business.

Management and boards of directors will need to answer many complex questions:

- How does a corporation practise “social distancing” when not everyone can work at home (think manufacturing, hospitals, retail)?

- How can a company cope with radical decreases in demand (think hotels, airlines, oil and gas)?

- When production rates go down (think automotive manufacturing), how should companies treat their workforces?

- How can companies maintain robust supply chains when they can’t place any orders in the short term?

- How can companies satisfy specific covenants relating to their debt and manage the risk of default?

- If corporations address the interests of these other stakeholders, what does that mean for the shareholders – especially when these shareholders constitute the principal assets in everyone’s pension plans and retirement savings plans?

In what seems like a millennium ago, 181 CEOs of the U.S. Business Roundtable announced last August that they were disavowing shareholder primacy in favour of addressing the needs and interests of all stakeholders.

With the landmark 2008 BCE decision by the Supreme Court of Canada, corporate Canada already has the legal infrastructure it needs to account for the variety of often conflicting stakeholder interests. It held that the board of directors must act in the best interest of the corporation – a decision that gives boards of directors all the legal tools they need to address the needs of all stakeholders affected by their companies’ operations.

Yet, while the court held that “the duty of the directors to act in the best interests of the corporation comprehends a duty to treat individual stakeholders affected by corporate actions fairly and equitably,” the BCE decision was, in the end, a “board-friendly” decision. It would ultimately defer to the “business judgment rule,” providing that the directors’ decision is found to have been within the “range of reasonable choices that they could have made in weighing conflicting interests.”

The pandemic may cause us to rethink what a “reasonable choice” might be.

Historically, the determination of whether a board is discharging its duties responsibly has been assessed with reference to whether its actions would be consistent with general common practice. But the pandemic highlights that common practices, such as payment of extraordinary dividends or buying back shares that favour the shareholder, may have disadvantaged many other stakeholders in the past.

What does it mean to treat all stakeholders fairly and equitably? And how then does the corporation organize itself to respond to these unprecedented circumstances? We believe that companies should come up with a set of principles and practices to help them navigate these choices.

Setting up principles

Every choice that a board or management makes has trade-offs between the stakeholders embedded in it. The question is: how to break those trade-offs, or what to do when you can’t? In these circumstances, and especially at this moment of pandemic, we argue that the bottom line should not take priority but rather the sustainability of the corporation.

At the extreme, the current crisis may cause some corporations that are overleveraged to “hit the wall.” Even with the government supports being proposed, long-term sustainability may not be possible. Even here, the board should give serious consideration to human issues, such as stability of employment for workers.

Constructive practices

Boards can develop explicit and coherent plans for addressing the tensions created by trade-offs and standards for resolving competing stakeholder interests. We recommend that boards create social responsibility committees, much like audit committees and compensation committees that are already in place, to dissect the relationship of their corporations to their stakeholder groups. For companies that already prepare corporate responsibility reports (about half of TSX-listed companies do), this information is a good starting point.

To truly understand the trade-offs that company choices and operations create, the boards will likely have to engage directly with stakeholders to understand their needs and work collaboratively to generate resolutions to trade-offs. In the short term, these committees should enable corporations to be nimble and to move quickly to deal with the volatility generated by the pandemic.

These principles and practices would enable boards to see this crisis as an opportunity to explore innovative solutions that might be better for everyone, or for many.

Being forced to think hard about the needs of stakeholders may generate ideas that would not have been considered in the past. Addressing these trade-offs thoughtfully can be a source of organizational transformation. For example, many companies have managed to “keep the doors open” – providing continued employment for their employees – by altering their product offerings: hand sanitizers instead of whisky, protective gear instead of auto parts, takeout food instead of table service.

We are also discovering that new “work from home” practices are more inclusive for many people with disabilities, creating new methods for increasing workforce diversity. Telecommuting may help improve long-term efficiencies in the healthcare system, avoiding unnecessary trips to the doctor just to get a prescription, for example. Reductions in trade may shorten our supply chains, keeping our economies local.

Initiatives such as these reflect creativity and sensitivity in dealing with stakeholders. Shareholders may have to be patient to enjoy the benefits of this creativity.

In simple terms, the board has to act in the best interest of the corporation. The best interest of the corporation is not just to increase share price but to position the corporation to achieve its purpose: to continue in business. Maybe this crisis is, when it comes to corporate governance, a blessing in disguise: will it be the one that will finally gets Canadian companies to manage beyond the pressures of quarterly earnings calls and short-term stock performance?

Research suggests that companies with better performance on corporate social responsibility are also those that weather crises more successfully. At a time of crisis, trust from stakeholders is what really matters and is earned over time. These stakeholders may prove to be a better lifeline than any government crisis subsidy.

Acting in the interest of the corporation sounds simple, but it is far from simple. It requires a board that is knowledgeable, diligent and willing to use its best efforts to treat all stakeholders fairly. Boards that use this challenge as an opportunity to drive innovation will create the greatest success for the companies they guide.

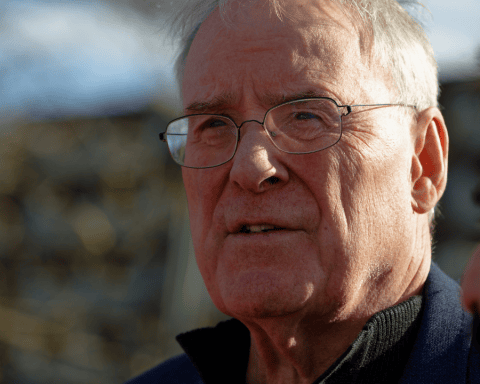

Peter Dey is the chairman of Paradigm Capital and the author of the 1994 report “Where Were the Directors?”

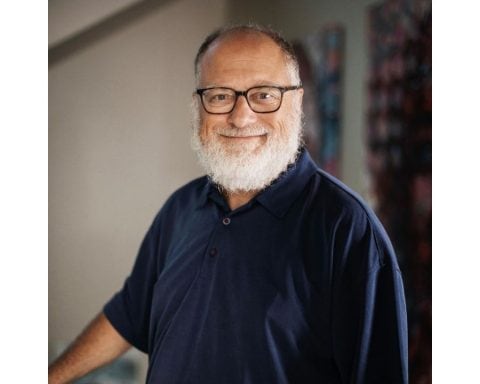

Sarah Kaplan is a distinguished professor at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management and author of The 360º Corporation: From Stakeholder Trade-offs to Transformation.