I recently attended our first neighbourhood swap event, a chance for our community to get together and trade clothes. Afterwards, the leftover clothes were wrapped up and given to a charity – most of it still in quite good shape but too small, too short, the wrong colour or maybe no longer in vogue.

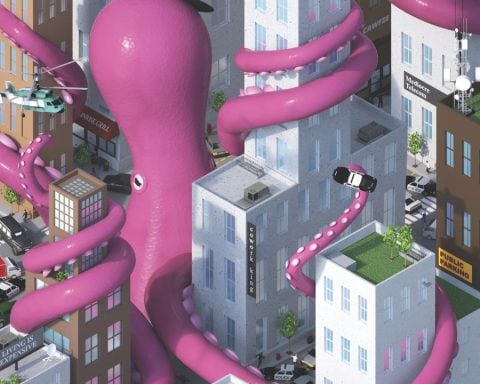

One of the biggest misconceptions that consumers have is that we should only donate clothes that are gently used. Ninety per cent of all people in Ontario donate at least some of their clothes, but whenever we have a pile of unwanted clothing we sort it based on what we imagine to be valuable and donate only the “good” stuff. The rest goes into the waste bin. Fifteen per cent of all unwanted garments are collected while the vast majority, 85 per cent, ends up in our landfills, taking up valuable space, releasing methane and toxic leachate and contributing to climate change.

This 85 per cent figure became surreal when the owner of a state-of-the-art textile sorting and recycling facility outside of Toronto informed me that he had to close his facility for two months because he couldn’t get enough used clothing – not from individuals, charities or private collectors. In fact, he has resorted to buying unwanted garments from the U.S.

Canada is the seventh largest exporter of used clothing in the world, with exports topping $185 million annually to places like Kenya, Angola, Tanzania and India. It turns out we’re also importing used clothing. Findings from the United Nations Comtrade Database show that imports from the U.S. reached $104 million (U.S.) in 2013 alone. Canada is by far its biggest customer in terms of used clothes, outpacing even Chile ($61 million) and Guatemala ($55 million). We throw our used clothes into the landfill only to turn around and buy used clothes from our neighbours. Stranger still, more than half of the used clothes exported by Canada is not originally from Canada but from the U.S.

Clothing collection is big business worldwide. For example, each year, the Canadian Diabetes Association collects more than $10 million in Canada alone from used textiles. Charities collect unwanted textiles as fundraising opportunities, which finances their missions as it diverts textiles from the landfill. But there is currently a gap in the amount of material that is collected versus what could be collected, and charities should consider the environmental impact of the goods they collect and choose not to collect.

Municipalities also need to step in and close this gap. While every municipality with populations over 5,000 must operate a blue box recycling program, textiles are on the supplementary list. Yet used clothes are often more valuable than many of the other item categories collected by municipalities. So why are textiles forgotten on our municipal waste diversion list? The good news is that all textiles can be reused or recycled in some way, with pioneering R&D efforts underway to ensure this happens.

This May, the Textile Diversion Strategies and Extended Producer Responsibility Symposium took place in Markham, Ontario, bringing together delegates from Canadian municipalities, recyclers, charities, academics and private companies to improve textile diversion. There was unanimous agreement that the most important step is to get more textiles out of our landfills.

The symposium’s location was no coincidence. Markham adopted a pioneering role in collecting and diverting textiles from its landfill after a waste audit revealed that textile waste accounted for six per cent of its total. Funded by a grant from the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, Markham has developed new esthetically pleasing, high-tech donation boxes. These boxes will soon be placed at safe and supervised spots, namely at all local fire stations.

Markham has partnered with The Salvation Army to deliver a clear message: “Every garment is welcome, no matter the condition.” This call also includes textiles such as towels and bedsheets, and even single shoes. The only request is the material should be dry, because humidity can lead to mould.

Households aren’t the only source of textile waste. Just imagine hospitals, hotels and all places where employees wear uniforms. According to a waste audit conducted in Nova Scotia, textiles accounted for 10 per cent of the residential waste stream and 11.5 per cent of the industrial stream. These numbers were so high that it led the province to debate a ban on textiles in its landfill.

I recently received a phone call from a woman involved in waste management in British Columbia, asking me what she should do with her clothes that are not good enough for donations. “Is this recycling initiative now everywhere in Canada, or only in the east?”

The answer is that textile recycling takes place everywhere in Canada and every consumer can donate textiles of any condition even if this message is not provided by the local government, municipality, charity or private collection company. I would advise every consumer to choose one charity or private collector and give them everything – the good and the bad.

While some pieces will earn the organizations more and others less, this mixture will contribute significantly to their revenue streams as well as lessen the load on our landfills.